On October 11, Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid an interesting tribute to Jayaprakash Narayan on his birth anniversary. The PM honoured the socialist leader, describing him as one of India’s most fearless voices of conscience and a tireless champion for democracy. On X, Modi posted a video discussing the constitutional values that Narayan stood for. The Prime Minister recalled that the “Loknayak” spent several days in solitary confinement during the Emergency, sharing a page from Narayan’s memoir, Prison Diary. An excerpt read: “Every nail driven into the coffin of Indian democracy is like a nail driven into my heart.”

Under Modi’s rule, scores of activists, lawyers, scholars, artists and dissenters have been detained under stringent laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), for their involvement in human rights advocacy, protests against caste violence, or alleged links to banned political groups. Like JP, the political prisoners have produced an impressive body of work—full-length books, essays, letters, poems, and notes—either during their imprisonment or after bail, criticising state repression and shrinking democratic space.

N.D. Pancholi, 81, a founding member of Citizens for Democracy and the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL)—both organisations founded by Narayan and others during the Emergency—drew a sharp distinction between the Emergency years and today. He called the present situation an “undeclared Emergency”, which is far more destructive than the one India witnessed under Indira Gandhi.

“Even during the Emergency, we could hold meetings in auditoriums criticising the government,” he recalled. “Indira Gandhi declared elections and allowed the Election Commission to function freely. That’s how people voted her out. Today, the Election Commission has been turned into an arm of the ruling party. People no longer have faith in it.” The loss of institutional independence and the criminalisation of peaceful protest, he warned, indicate a bigger crisis of democracy than any India has faced since Independence.

Also Read | Book Review: ‘Why Do You Fear My Way So Much?’ by G.N. Saibaba exhibits a fearless mind

How Long Can the Moon Be Caged? Voices of Indian Political Prisoners (2023), an anthology edited by Suchitra Vijayan and Francesca Recchia, compiles writings from political prisoners. Vijayan, in an interview with the magazine Mukoli noted that while the book documented 250 political prisoners, the list continues to grow. “India has always had political prisoners; the first appeared soon after independence. Under Modi, I view political prisoners as a tool through which a particular authoritarian, fascist politics is consolidated,” she said. “Look at who is arrested: student leaders, lawyers, journalists and activists. This is a politics of punishment and disappearance. First silence the most vocal, then criminalise anything seen as a challenge to the state.” She noted that Indian media avoids calling them “political prisoners”, instead labelling them “terrorists”, “anti-nationals”, or “urban Naxals”, amplifying biased narratives like a propaganda arm of the state and its corporate allies.

While incarcerated in Taloja Central Jail (April 14, 2020, to November 26, 2022), scholar and public intellectual Anand Teltumbde penned essays, articles, and reflections that form the core of The Cell and the Soul: A Prison Memoir (published in 2025). The book critiques the Modi government’s economic policies, details the dehumanising conditions of prison life, and explores the psychological toll of incarceration. Teltumbde told Frontline in a recent interview that his memoir continues the tradition of prison memoirs from Dostoyevsky’s Notes from a Dead House to Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom. It discusses the cracks in the process that sent the BK-16—the group of 16 activists, academics, lawyers, and writers arrested in connection with the Bhima Koregaon-Elgar Parishad case—to prison, the police’s methods, and the cruelty that claimed the lives of his fellow inmate Bhola Singh and Father Stan Swamy.

Sudha Bharadwaj, in her memoir From Phansi Yard: My Year with the Women of Yerawada (Juggernaut, 2023), recounts her 15 months in Yerawada Jail, showing the state’s consistent failure to uphold justice while celebrating the extraordinary strength of the women confined within prison walls.

Marking six years since the 2018 arrests in the Bhima Koregaon case, The Polis Project, a New York-based digital magazine, published a series of writings in 2024 by the BK-16, including Arun Ferreira, Gautam Navlakha, Hany Babu, Jyoti Raghoba Jagtap, Mahesh Raut, Ramesh Murlidhar Gaichor, Rona Wilson, Sagar Tatyarao Gorkhe, Shoma Sen, Stan Swamy, Sudhir Dhawale, Surendra Gadling, Varavara Rao, and Vernon Gonsalves.

Their accounts resemble what senior BJP leader and Defence Minister Rajnath Singh recalled in a media interview last year. Reflecting on his imprisonment during the Emergency, Singh said, “Democracy was strangulated under Indira Gandhi’s rule. I was 24 when I was thrown in jail for 16 months for opposing the Emergency. We created awareness among people about how it was dangerous and reflected a dictatorial tendency.” His mother suffered a brain haemorrhage and died while he was in jail. “I did not get parole. My brothers performed the last rites,” he said, hitting out at the Opposition for calling the Modi government “dictatorial”.

In the 2002 album Samvedna, sung by ghazal maestro Jagjit Singh, former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee references the Emergency, describing it as a dark era of silenced dissent and denied constitutional freedoms. “The entire country had been turned into a prison. Freedoms had been abducted. People in large numbers had been arrested and jailed,” Vajpayee says as a prelude to his song, Aik Baras Beet Gaya, vividly capturing the oppressive atmosphere of 1975.

Stan Swamy wrote several letters and statements from Taloja Central Jail before his death in July 2021. He died on July 5, 2021, in a Mumbai hospital while in judicial custody, succumbing to health complications including Parkinson’s disease and cardiac arrest, exacerbated by inadequate medical care. In one of his notes on the plight of undertrial prisoners, he described how “many of such poor undertrials don’t know what charges have been put on them, have not seen their charge sheet and just remain in prison for years without any legal or other assistance,” ending with the defiant line, “But we will still sing in chorus. A caged bird can still sing.”

Telugu poet and activist Varavara Rao, 84, on regular bail in Mumbai since August 10, 2022, on medical grounds, critiqued the term “correctional institutions” as a misnomer. Prisons, he argued, are institutions of sadism, dehumanisation, and corruption. “The jail officials, however, understand the prisons as actually envisioned by the state, and they act accordingly. They become perverse, cynical and sadist—as the state expects them to,” he wrote. “Of late, with the connivance of the Central government, custodial deaths of political prisoners in jail have become a policy and practice of the Maharashtra government.”

An article on The Polis Project, written by the parents of Sagar Gorkhe, a Dalit artist and member of the Kabir Kala Manch cultural troupe, who was arrested in September 2020 and remains incarcerated in Taloja Central Jail, Mumbai, argues that police have given a bad reputation to the troupe. “Is it a crime to sing songs now?” they wrote. “We just want him to be out before we die.”

Professor G.N. Saibaba addressing a press conference in New Delhi following his release from the Nagpur Central Jail after the Bombay High Court acquitted him in an alleged Maoist links case, on March 8, 2024.

| Photo Credit:

SHASHI SHEKHAR KASHYAP

The parents of Ramesh Gaichor, an anti-caste activist and a performer at the cultural organisation, Kabir Kala Manch, claimed that their son has been framed. “We have to suffer like this at this age. We are waiting for him to get free. We want to meet him once before we die. This is our last wish,” they wrote. The Bombay High Court granted Gaichor a three-day temporary bail on August 26, 2025, to visit his ailing father, but Taloja jail’s procedural error delayed his release until September 10, leading to an apology and bail extension until September 13.

Both sets of parents complain that their sons never visited Koregaon Bhima, where the riots occurred, and are unable to understand the alleged connection between the Elgar Parishad and those riots.

Also Read | The 16 activists arrested in relation to the Bhima Koregaon case are victims of witch-hunt

Former Delhi University professor G.N. Saibaba, acquitted by the Bombay High Court on March 5, 2024, after over a decade in prison for alleged Maoist links, revealed that he endured torture in Nagpur Central Jail. The 58-year-old, with polio-related disabilities, told media in Delhi on March 8, “The inhuman treatment meted out to me during the imprisonment, which amounted to torture, put my life at risk. I was denied medical care on several occasions. It has left me a physical wreck.”

Arrested in 2014 under UAPA and for criminal conspiracy, he said, “My mother, despite being uneducated, made every possible effort as she brought me up and made sure that I got educated. She would take me to school in her arms. But I was refused permission to meet my dying mother or perform her last rites.” His mother died in August 2020. His lawyer, Surendra Gadling, was falsely implicated in the Elgar Parishad case (alleged Maoist links to an event in Pune on December 31, 2017) and denied medication. Pandu Narote, a 33-year-old tribal co-accused, died in 2022 after delayed medical care. Saibaba died on October 12, 2024, owing to health issues aggravated during his incarceration.

“What we face today is not just authoritarianism. It is ideological repression,” said Pancholi. Despite her excesses, he said, Indira Gandhi retained a certain measure of conscience shaped by her father’s legacy and the freedom movement. “Within 19 months, she realised her mistake. She cared about how the world saw India,” he observed. “Today’s rulers have been in power for over a decade and remain unmoved by either world opinion or the condemnation of progressive voices abroad.” While the Emergency was not communal in nature, he added, “the present regime is systematically dividing society along religious lines, marginalising and excluding entire communities.”

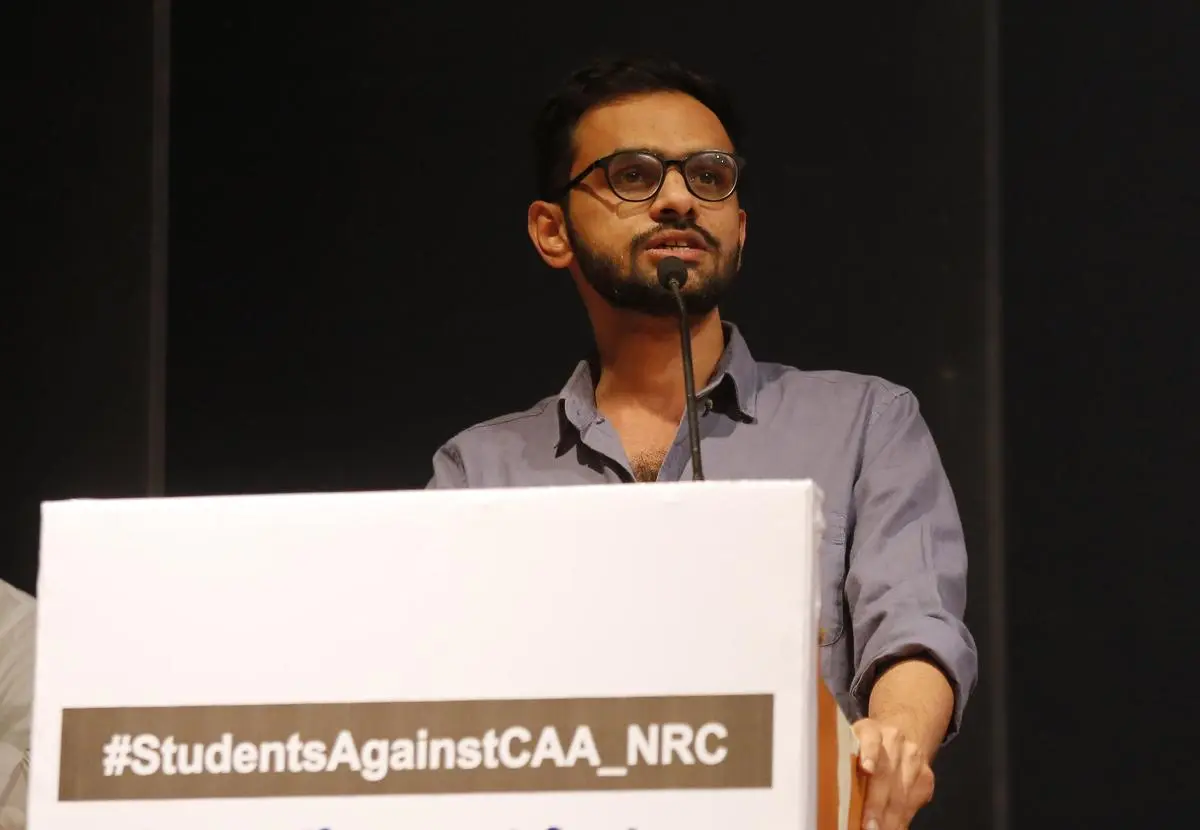

The wait for justice continues for many. Umar Khalid, a student activist and former JNU scholar who has been in jail since September 2020 without a substantive trial, as an accused under UAPA of being a “key conspirator” in the 2020 Delhi riots, wrote from Tihar Jail in June 2025, reflecting on his five years of incarceration without trial. “Five years have passed, almost. Half a decade. That’s time enough for people to complete their PhDs and look for jobs, time enough to fall in love, marry and have a baby, time enough for one’s kids to grow beyond recognition, time enough for the world to normalise the genocide in Gaza, time enough for our parents to grow old and feeble,” he wrote, wondering, “Is it time enough for our release?”

Student leader Umar Khalid speaking at the Chhatra Bharti seminar held in Y.B. Chavan Centre, in Mumbai, on January 5, 2020.

| Photo Credit:

EMMANUAL YOGINI