The bars were being traded in Seoul’s basements long before the world was listening. What began in dimly lit clubs and backroom battles has now exploded into a global sensation, with Korean hip-hop’s DIY ethos and streetwise sensibility forging a unique sonic identity.

From legendary names like Seo Taiji and Boys, Tiger JK and Jay Park setting the stage in its early days, to heavyweights like RM, Suga, J-hope, and Zico giving it a spin of their own, Korean hip-hop has come a long way. It has evolved from a borrowed sound to a powerful voice. It’s a story of different cultures coming together, and a very passionate community that refuses to be silenced.

The Seeds of Change

In the late 1980s, a new sound seeped into Seoul. It wasn’t exactly a local thing – it was a spillover effect of American hip-hop brought in by army officers stationed at the US military base in Yongsan and the expat hangouts in Itaewon. As Korean youth got hooked onto it, hip-hop soon made its way into Seoul’s underground clubs. Local artists began to feel the beat, absorb the rhymes, and interpret it in their own way. And that’s how Korean hip-hop took off as a homegrown hip-hop movement with a fresh crop of talent ready to take the stage.

A new era dawned when rock legend Hong Seo-beom made his music debut, leading the rock band Oxen 80. Hong is often credited with pioneering Korea’s rap scene with his 1989 song “Kim Sat-gat.” It’s Hyun Jin-young, however, who planted the seeds of hip-hop music in Korean culture. According to an Across The Culture report, it was Hyun’s dance skills that piqued the interest of SM Entertainment’s (then known as S.M. Studio) founder Lee Soo-man, leading to a year-long mentorship under his guidance as the agency’s first signed artist. A year into his training period, Hyun debuted in 1990 with the album New Dance 1, featuring the breakout hit “Sad Mannequin.” While Korea wasn’t quite ready for his distinct style of music just yet, his infectious energy, oversized fashion, and cool rapping made him a star on the rise. It also foreshadowed the arrival of something that would blow up to become one of Korea’s biggest cultural exports—K-pop.

The Cultural Significance

At the time, a popular club in Seoul called Moon Night was at the heart of the city’s music scene. Like oil on a canvas, it fueled a new era of artistic expression, quickly emerging as a hotspot for young artists to connect, trade ideas and push the boundaries of music. Sound of Life says that it was Moon Night where “the fusion of hip-hop from the US and South Korean cultural elements began to form.”

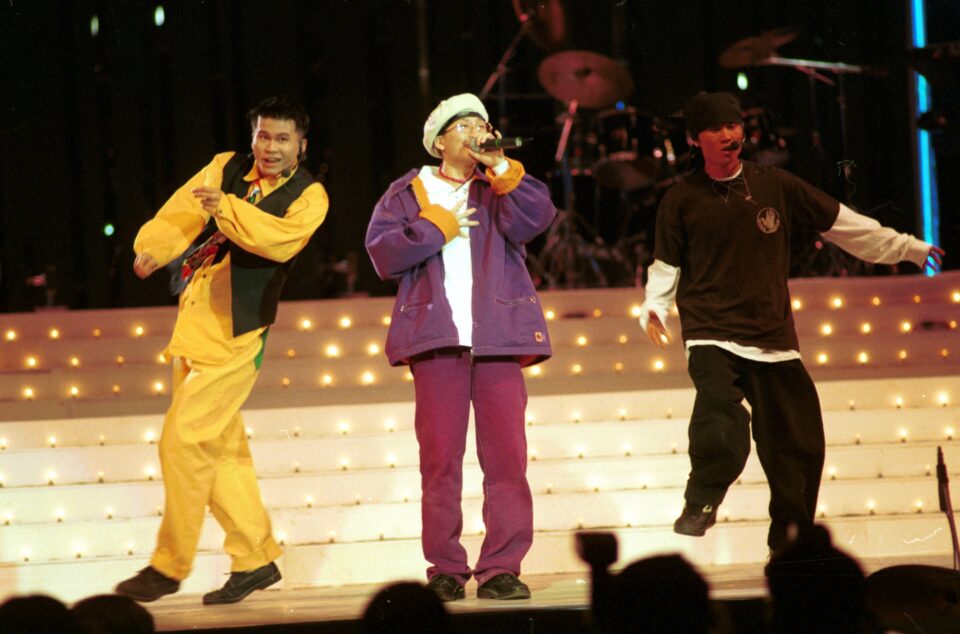

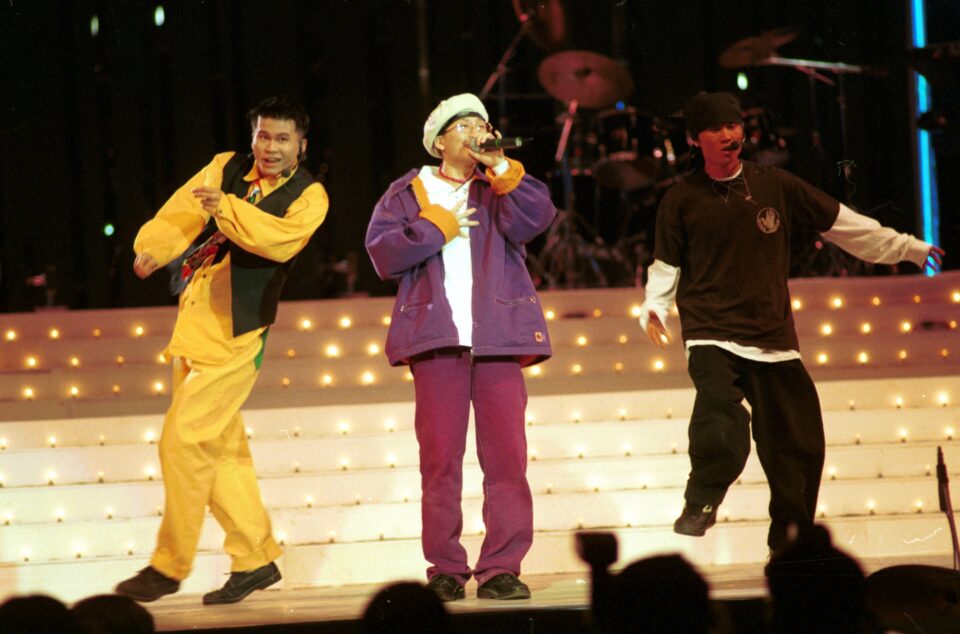

Moon Night’s walls witnessed the rise of Seo Taiji and Boys, Clon, and Deux, some of the most influential Korean acts in the early 1990s, who found their voice in hip-hop music. Yang Hyun-suk, the founder of YG Entertainment, was among the club’s most talented dancers during that time, and his experience at Moon Night apparently shaped his vision for K-pop. In essence, Moon Night was a giant influence, laying the groundwork for the three heavyweights in Korean entertainment—SM, YG, and JYP—and, as Laist notes, standing out as “the incubator of what contemporary pop music is for Korea today.”

Mainstream Momentum

Korean hip-hop truly gathered steam between the late 1990s and early 2000s. The underground scene in Seoul’s Hongdae took off with clubs like Master Plan hosting the likes of Drunken Tiger, Verbal Jint, Dynamic Duo, and Epik High. And while the crowds were erupting to their raw bars and mic-ripping dexterity, along came online webzine Hiphopplaya. The new media format brought together a community of fans and artists by sharing new music, insights, and conversations that got people more immersed in hip-hop culture. The genre gained more traction with the reality show Show Me the Money. Korea couldn’t get enough of its first hip-hop-centric television series, as rookies and experienced rappers battled for bragging rights. Music journalist and entrepreneur Riddhi Chakraborty, who has been reporting on K-pop, hip-hop, and R&B for nearly a decade, credits its “massive virality” as the first-of-its-kind TV show on Korean hip-hop for driving the sound mainstream. “Show Me The Money began to introduce mainstream audiences to some really talented rising names, including Loco, BeWhy, Sik-K, Lee Youngji, and Huh.” Its debut in 2012 was surely a catalyst for the Korean rap revolution, with spin-offs like Unpretty Rapstar (2015) and High School Rapper (2017) becoming platforms for young and aspiring artists.

At the same time, the rise of independent record labels like Illionaire Records, AOMG, and H1ghr Music, established by industry veterans Dok2, The Quiett, and Jay Park, revolutionized the Korean hip-hop and R&B scene. They prioritized artistic freedom above all, showcasing talents like Beenzino, Gray, Code Kunst, and pH-1. Riddhi notes that these labels promoted a community-driven approach, treating artists like family. “The core foundation of hip-hop lies in building relationships like these via collabs and working on projects together and forming similar ideals— it led to the network of artists growing and therefore exposing more and more audiences to the web of Korean hip-hop.” She also attributes the industry’s growth to a lot of idol rappers who excelled in the craft and inducted pop listeners into the hip-hop landscape. “BTS, Stray Kids, BigBang, and CL are some of the key names in this aspect, and their contributions have been massively impactful,” she adds.

K-Hip-Hop and K-Pop

K-pop is deeply rooted in hip-hop. Its rhythms, style, and wordplay have become the standard, making it a fundamental part of the K-pop identity. AOMG CEO Yoo Deok-gon told CNA Lifestyle, “Hip-hop has that ‘coolness’ that comes from fashion and freedom.” This uniqueness was a major draw in influencing K-pop, with many rappers transitioning to idol groups. Think of BigBang’s G-Dragon and T.O.P, once a part of Korea’s underground rap scene, or BTS’s RM, who started as Runch Randa in the underground hip-hop scene before becoming K-pop idols. Yoo elaborated that regardless of whether an idol group has four or five members, their music isn’t complete without rap, adding that K-pop’s growth owes a lot to the genre.

However, it’s a complex dynamic between the two. Some see K-pop’s global success as a catalyst for K-hip-hop’s growth, with examples like “Korean hip-hop stars collaborating with K-pop stars and being introduced to their global audiences (think about Tablo and RM, or Taeyon and Crush, or G-Dragon and Zion.T)” as Riddhi notes.

Others argue that this crossover dilutes the genre’s authenticity. Zeo, a budding rapper from Busan, tells Rolling Stone India, “Authentic hip-hop can’t be silenced, and you just can’t sleep on it. Korean hip-hop’s soul is in the underground. Commercial success might bring fame, but it’s the realness that resonates and will always rise above the noise.”

Breaking Boundaries

The global expansion of Korean hip-hop gained further momentum through strategic musical collaborations. G-Dragon and Missy Elliott’s “Niliria” in 2013 is a fitting example of this. The Korean folk music layered with beats and rap lines was a refreshingly new sound that screamed savage attitude and sparked the curiosity of a diverse audience worldwide. In 2015, Keith Ape’s song, “It G Ma,” with JayAllDay, Loota, Okasian, and Kohh, exploded online, amassing millions of views on YouTube. The song’s jarring intro, innovative sound design and celebration of cultural pride were among its biggest highlights, making it a significant voice in East Asian hip-hop. That same year, CL of 2NE1 collaborated with Diplo, Riff Raff, and OG Maco on “Doctor Pepper,” underscoring the genre’s versatility.

A new record was set in 2016 when Epik High performed at Coachella, marking a historic moment as the festival’s first Korean act. Jay Park too scored a big win in 2017 when he signed with Jay-Z’s American record label Roc Nation and released his single “Soju” featuring 2 Chainz in 2018. It was Park’s American debut, but one that triggered a chain reaction for future collaborations with supergroups like BTS joining forces with global superstars like Coldplay, Nicki Minaj, and Steve Aoki.

The time was witnessing a growing recognition of Korean hip-hop, and MBC, Korea’s prominent broadcasting network, saw an opportunity to ride the wave and launched Show Billboard – Kill Bill in 2019. A competition among Korean hip-hop artists for a coveted global collaboration, the program’s success proved to be a game-changer, moving the needle of Korean hip-hop worldwide.

Music with Purpose

The genre has been venting emotions head-on—letting out frustrations, challenging the norms, and proudly flexing its individuality. In a society that’s about conformity, Korean hip-hop artists are daring to redefine what it means to be Korean. For many young Koreans, hip-hop is a way to express the anxiety and pressure of living in a world that’s obsessed with perfection. Seulgi, a street dancer from Hondae, says, “Hip-hop speaks to me, and I feel seen in their stories. When it comes to music, I’m not looking for polished, cookie-cutter flows; I’m looking for real talk and real emotions.”

Seulgi’s sentiments echo through various artists’ expressions of the genre. In a previous interview with Rolling Stone India, Bibi, the multifaceted Korean singer, rapper, songwriter, and actress, said, “I think the honesty of hip hop – especially in the lyrics – was something I was drawn to.” Similarly, Chloe Young of the Korean girl group Badvillain, known for their hip-hop roots, says, “I believe that Korean hip-hop is a genre that has grown through artists expressing their stories with honesty and in their own voices.”

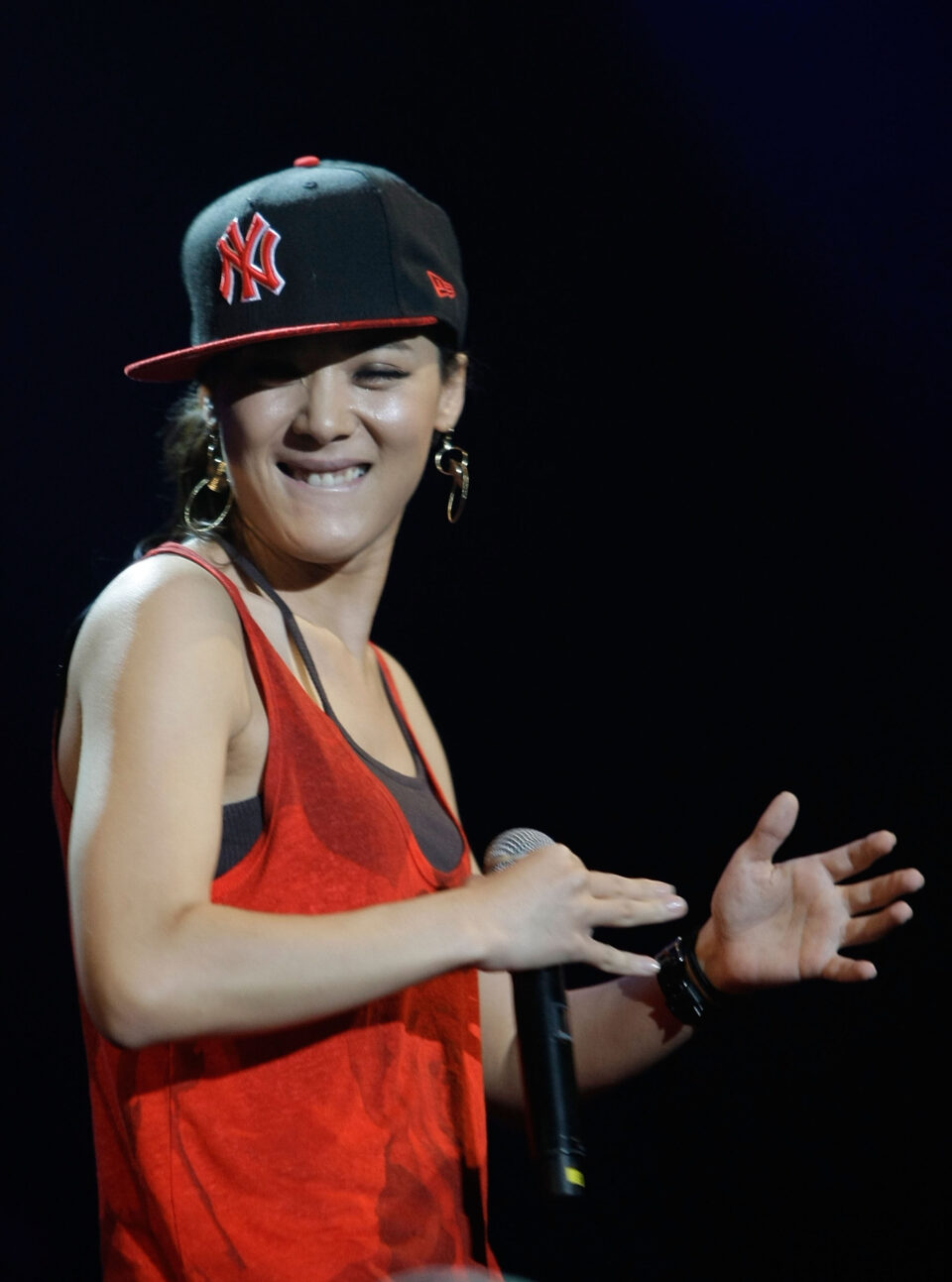

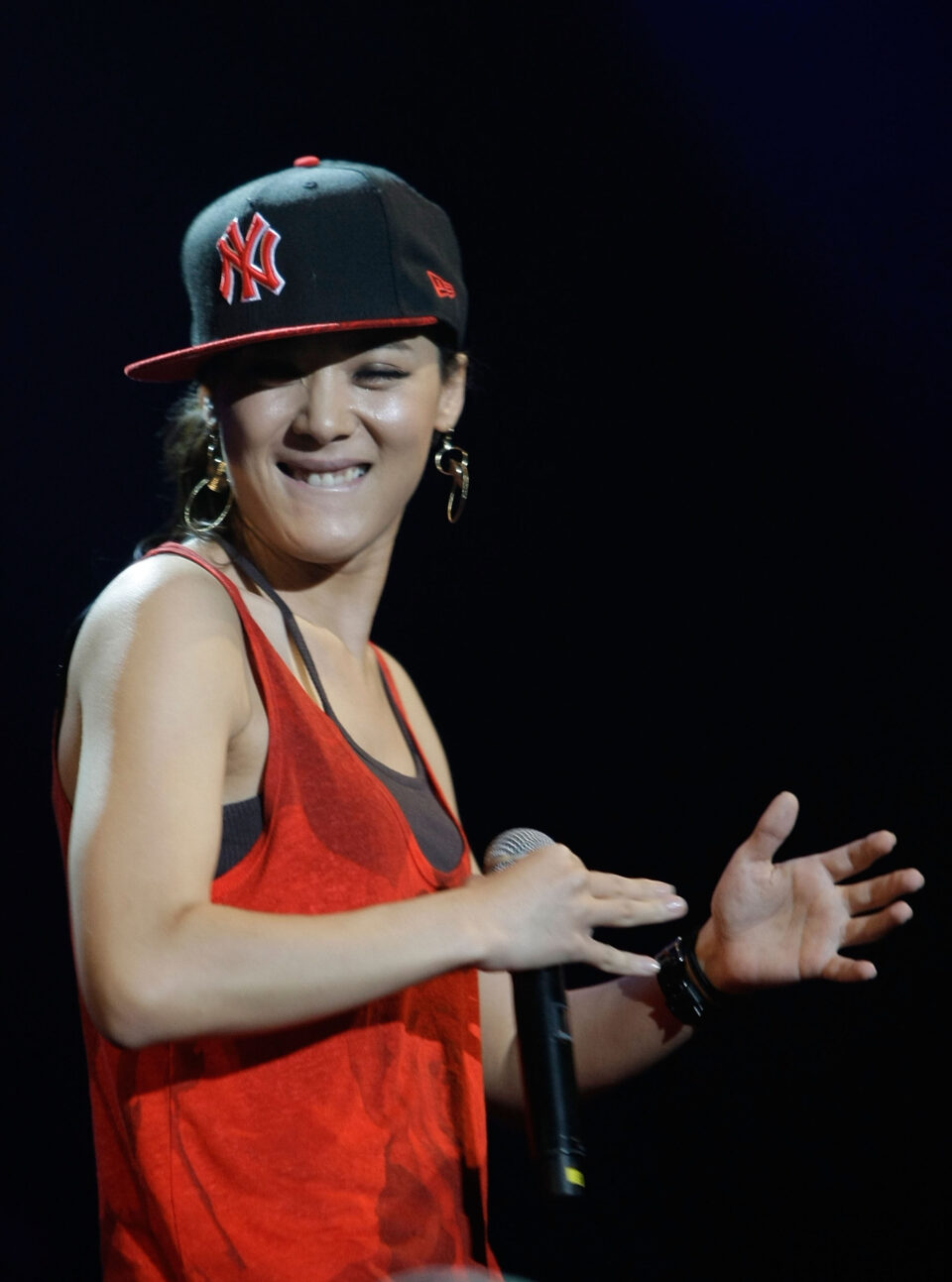

The legendary Yoon Mi-rae, a rapper and artist, has been one of the genre’s most fearless voices. Her music is a raw, candid portrayal of the struggles she’s faced while growing up in Korea, due to her multicultural background. Songs like “Black Happiness” powerfully capture the pain, the anger, the frustration she went through, reflected in lyrics like, “My skin was dark from my past/People used to point at me/Even at my mom/Even at my dad, who was black, and in the army…Music doesn’t judge color/They give me light/I lead my music/We lean on each other.” Likewise, artists such as PSY have used their platform to skewer the excesses of Seoul’s wealthy elite, as is the case with his iconic hit “Gangnam Style,” a searing satire of the Gangnam district’s materialism and superficiality.

In Epik High’s diss track “Born Hater,” featuring rappers Beenzino, Verbal Jint, B.I, Mino, and Bobby, they take down online hate machines, calling out the anonymous cowards who fuel the fire. Agust D (Suga of BTS) in “Daechwita” dissects the costs of success, BTS rips apart apathy towards social issues in “Am I Wrong,” and (G)I-dle (renamed I-dle) in “Nxde” blasts the objectification of women. Songs like these have invariably challenged wrongs, addressed what’s relevant, and, most importantly, questioned Korea’s traditional Confucian values, sparking conversations about identity, society, and change.

Future and Emerging Trends

With a sound that’s evolving with each new release, the horizon is glowing with promise. K-hip-hop is more eclectic than ever, drawing on diverse influences, from trap and Afrobeat to boom-bap and lo-fi. Artists, including Ash Island and Skinny Brown, are at the forefront, putting forward creative expressions that are both personal and relatable. And the best part? Social media is leveling the playing field, letting artists connect directly with fans and share their music freely. In tandem, online shows like Mic Swagger are repping freestyle rap, keeping the creativity flowing and the excitement alive.

The anticipation is building with BTS’s upcoming album, expected to further elevate K-pop’s global presence and keep creating opportunities for hip-hop collaborations. 1300, Lee Youngji, JMin, Luci Gang and indie artists of sorts continue to experiment with the genre, previewing the emergence of new subgenres. Bibi, Jay Park, Jessi and more are playing at iconic music festivals like Rolling Loud, highlighting hip-hop’s global appeal and the rising renown of Korean hip-hop. It only makes sense, then, that international tours and festival performances are likely to become more frequent in the coming days. To make matters more interesting, virtual idols like Plave are taking the scene to a whole new level, showing that technology is going to play a huge role in shaping the future of music. This evolution is precisely what Zeo captures when he says that the next chapter in Korean hip-hop “is being written with every release, every collaboration, and every [bold] experiment.”